“Is your foot sore?”, I innocently asked. Part way through a session I noticed my client pressing her foot into the floor. She played sports and regularly sustained injuries. The dissociative capabilities she developed as a child to attempt to protect herself from severe abuse and neglect meant she had a high pain threshold. She often didn’t register pain unless an injury or symptom was severe. This at times resulted in aggravation of injuries which prolonged recovery.

Her face froze. She looked like the proverbial deer caught in the headlights. Her expression was a combination of shock (at my noticing) and shame (for something of which I had no idea). I was perplexed by her reaction. I sat quietly and waited. After a few seconds she replied, “No. I have a thumb-tack in my shoe and I’m pressing my foot down on it.” “Oh,” I said, “why are you doing that?”. “Because it helps me distract from what we’re talking about,” she replied.

My client disclosed that she frequently did this in sessions. How had I not noticed before? She went on to explain that it was a great way to calm or distract herself when our conversations were triggering, and she felt overwhelmed.

The fact that my client regularly self-harmed was not news. We had worked together with various self-harming and extreme risk-taking behaviours, including exploring drains underneath the city centre and riding on the top of moving trains. Over time these activities had reduced in frequency and intensity. Self-harming in session, however, was news to me.

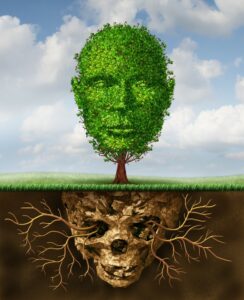

Trauma therapists understand that a common sequelae of early childhood trauma and abuse is self-harming behaviour. As paradoxical as it may seem, what on the surface appears self-destructive and self-sabotaging serves a variety of survival functions, one being mood state regulation. This is what my co-author, Colin Ross, MD., and I describe as ‘the problem is not the problem but a solution to another problem’. Common reasons clients self-harm include:

- Trance logic; the client takes control of inflicted pain and hurts themselves before someone else hurts them. This creates the illusion of “I’m in control”; or it may be to let out the badness inside.

- Self-harm can assist in reducing rising tension, anxiety, panic and fear. It produces a sense of calm as endorphins are released.

- Pain helps the person feel connected to their body when they are numb and shut down.

- Pain may compensate for feelings of emptiness. Feeling pain is better than feeling nothing. It helps the person feel real and alive. The blood is proof of their existence.

- Self-harm can assist in preventing suicide. This seems counter-intuitive. Extreme self-harming behaviours may also escalate the risk of death and/or be a precursor to suicidal intent.

- Hurting the body can change states of consciousness.

- Hurting the body may be motivated by a desire to control or punish self or another part of self (in dissociative identity disorder).

- In the same way that artwork can be a conduit to “tell without talking”, self-harm can be a way to express “I need help” without telling any secrets.

- Self-harm can be a “safe” outlet to express feelings such as sadness, grief, anger and shame.

- Hurting the body can distract from overwhelming emotions or physical pain.

- Self-harm can be a re-enactment of abuse, such as hurting parts of the body that were hurt during abuse, commonly the genital area.

- Sometimes a child may be taught to harm themselves by a perpetrator.

- Compulsion to self-harm can be triggered by contact with perpetrators or the anniversary of significant events.

- Self-harm may be iatrogenic (caused by therapy when the therapist is not aware that the pace of the work is overwhelming the client). It may be an expression of anger toward the therapist.

- Self-harm may be driven by secondary gain, for example, to become sexually aroused or seek attention. Clients sadly often experience hostility from mental health and medical professionals in emergency departments, with self-harm dismissed or labelled as “borderline” acting out.

The mechanism for self-harming behaviour may be as varied as the function. The term self-harm conjures up deliberate physical injury to the body, which is often how harm is expressed. However, it can also involve other behaviours that may not initially be understood as self-harming. Common self-harming behaviours and distractions from overwhelming internal experiences include:

- cutting

- burning

- scratching or picking skin

- pulling out hair

- head banging or hitting the body with fists or objects

- swallowing toxic substances or sharp objects

- pinching

- biting

- substance misuse or abuse

- binge eating and purging

- compulsive sexual activity such as masturbation or sex with a partner (this involves impulses and urges that are contrary to what the person may ordinarily seek or desire and may escalate feelings of self-loathing)

- gambling

- workaholism

- over-exercising

- compulsive shopping or overspending

- binge watching tv or game playing

Addiction, like cutting, is another means to regulate mood and self-soothe. In the words of Gabor Maté, “The question is not why the addiction, but why the pain.” The addict is a smart consumer making an intelligent choice at the supermarket of coping strategies: the macaroni in aisle two doesn’t provide much of a rush, but the opiates in aisle three certainly do. The addictive behaviour is self-soothing, kind, and based on self-love—the drug would be an unqualified blessing if it were not for its side effects and social costs. (Ross and Halpern, 2009).

Self-harming behaviour generates a great deal of distress for therapists (who feel powerless to help) and clients (who feel ashamed and powerless to stop). Therapists are understandably concerned for their clients’ safety. It is a therapeutic issue ripe for transference and counter-transference dynamics and activation of the victim, rescuer, persecutor triangle (a conversation for another day).

When the therapist sits with and soothes their own anxiety and fear about self-harming behaviour, and understands that they cannot and should not attempt to stop clients’ behaviour, it opens the door to fully engage with the meaning, purpose and function of self-harming, focus on building inner resources to soothe the dysregulated nervous system, develop compassion between parts of self (the harmer and the harmed) and step safely toward what is disowned and managed through harming the body.

Back to the client I mentioned at the beginning of this article. The conversation about using a thumb-tack to soothe herself went back and forth. We discussed the effectiveness of this strategy versus why she needed to hurt herself to distract from feelings arising in sessions. My reflections that if she needed to use this strategy it was a message to us both that the work we were doing was too much and too fast was dismissed out of hand. My suggestion that we needed to slow down, pull back and explore what was happening was met with frustration and irritation. The strategy worked fine, let’s get on with it (bull in a china shop approach to therapy).

When all my ideas, reflections and suggestions were rebuffed, I said, “You have been very open and honest disclosing the risky and self-harming behaviour that you engage in out of sessions and you’ve done some fabulous work around these issues. I know you harm yourself outside of sessions and you know I’m concerned about the risks and damage to your body. I haven’t suggested or asked you to stop. But, harming yourself in front of me, even though I haven’t been aware of it until today, has crossed a line. It’s not OK for you to hurt yourself in front of me.”

She looked me in the eye for several seconds digesting what I had said and then nodded. She removed her shoe, took out the thumb-tack and placed it in the waste bin. “I won’t do it again”, she said. I knew she would keep her word.

To explore self-harming behaviours and other trauma related therapy issues and approaches you can purchase Trauma Model Therapy: A Treatment Approach for Trauma, Dissociation and Complex Comorbidity, (2009), Ross, C. A. & Halpern, N. Manitou Communications Inc.

Please join me with Professor Emeritus John Briere, PhD in his upcoming two part online training on 6th and 13th May 2022: Treating Self-Injury And Sexual Compulsivity From An Attachment-Trauma Perspective

You may also like to learn more about trauma and addiction with Dr Eli Kotler: Addiction: the Mind’s Answer to Trauma

Guest Editor: Colin A Ross, MD