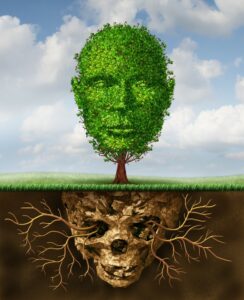

Indigenous cultures have utilised plant based medicinal and mystical properties for millennia. In western culture, psychedelics are often associated with the ‘Summer of Love’ (1967) when the media focused on the hippy counterculture that had been evolving in America and Europe over several years. It was seen as a dangerous movement that threatened law and order. In 1971, at a press conference, President Nixon declared drug abuse “public enemy number one … In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive”. Nixon’s ‘war on drugs’ effectively halted exploration of therapeutic benefits of psychedelics for decades.

Current psychedelic research includes clinical trials in MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of PTSD, alcoholism, and social anxiety. Psilocybin clinical studies have been conducted for depression, addiction and relieving emotional and existential distress at the end of life for terminally ill people. In this article I explore the current psychedelic research in Australia with Martin Williams, PhD, Executive Director of research charity, Psychedelic Research in Science and Medicine (PRISM). Martin has been involved in seeking approval for two clinical trials, one of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD, and the other of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of anxiety and depression associated with terminal illness. He is currently working with another interdisciplinary research group on a clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression.

Clinical trials are conducted by highly respected institutions, scientists and mental health professionals, yet there is a lingering public perception and mental health professional reservation that views it as fringe, not serious at best, and dangerous at worst.

In a move that has taken researchers by surprise, on 3 February 2023, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) announced approval of the psychedelic substances in magic mushrooms and MDMA for use by people with certain mental health conditions, specifically PTSD and treatment resistant depression. This makes Australia the first country in the world to recognise psychedelics as medicines.

Naomi: I draw a comparison to the current state of play in psychedelic medicine with the dissociative disorders field, and the ‘memory war’ of the 1990’s (False memory Syndrome – A short history). In any field there are professionals who behave irresponsibly, unethically and sadly, predatorially. These are the cases that draw media attention. The same has occurred in the psychedelic medicine field. It is easy to say let the science speak for itself, but we know that truth and facts don’t necessarily change public, political or professional opinion. What are your thoughts about this challenge to the field?

Martin: That’s an interesting comparison, although I certainly hope the implications in relation to psychedelic-assisted therapies are not so grave. Nonetheless, it’s critical for us all to be aware of the risks associated with psychedelic medicine – particularly given the well-recognised tendency towards suggestibility engendered by the psychedelic mental state – that have confronted the field over the past twelve months.

This said, it seems to me that there’s a clear trend toward black-and-white narratives emerging in the current conversation, which in certain ways reflects the situation in the 1960s that ultimately led to the (now broadly discredited) War on Drugs.

One problem with psychedelic science, reflecting the overwhelming challenge faced by science more generally, is that it takes time and resources to find answers to research questions – and in fact it often takes time to come up with the right questions themselves. This doesn’t sit well with people who (be they those experiencing mental health problems, or others who express an imperative to help them) seek quick and easy answers to life’s challenges, including mental ill-health. Add to this the notorious reticence of researchers to communicate publicly in tidy sound grabs and to promote their own positions, and the obvious consequence is an opening for loud voices and self-serving agendas to dominate the discourse.

An interesting contrast between the hippy era of the 1960s (and the very blunt legislative instrument employed by the Nixon administration and then the United Nations in response) on the one hand, and our current 21st-century situation on the other, is that despite some appearances, the broader socio-political context is now somewhat more nuanced… just as the golden era of Western movies is long gone, I feel the stark contrast between the “good guys” and their adversaries is now much more blurred.

In terms of its effects on our work at PRISM – which we founded to initiate and support psychedelic medical research in Australia over the last twelve years – I’ve seen a very interesting progression: from the early resistance on the part of institutions and the medical profession, we now observe a frenzy of excitement that, frankly, leaves us bemused and concerned.

Naomi: Psychedelic assisted psychotherapy is a broad term covering different drugs, used for different mental health conditions. Can you explain in lay terms how MDMA and psilocybin work on the brain and why MDMA is used for PTSD and alcoholism and psilocybin for anxiety, depression and addiction?

Martin: This is a fascinating area… there’s still much to be explored and clarified in terms of how psychedelic compounds act in the human brain, and then how those effects translate to therapeutic outcomes.

The first step is to differentiate between “classic” psychedelics such as psilocybin, and what I call “honorary” psychedelics such as MDMA.

The classic psychedelics bind directly to a class of serotonin receptors concentrated in certain areas of the human brain, and very specifically mediate the effects of those receptors. It’s a bit like unlocking a lock with a particular key, where the lock can differentiate among a range of various keys.

MDMA and related compounds act by flooding certain areas of the brain with serotonin, which is our own internal neurotransmitter that is the natural “key” to the corresponding serotonin receptors in our brains.

Thus, classic psychedelics such as psilocybin act differently from MDMA. By processes we are yet to clarify, psilocybin causes a series of neurological effects that result in a reduction in the activity of certain brain networks, and simultaneously the amplification of other networks. At the same time, connectivity can be enhanced among certain brain regions that aren’t normally in touch with each other. Our normal thought processes – particularly those that figure prominently in our everyday cognition – take a back seat, and others – particularly those resembling dream and meditative states – can dominate this altered state of consciousness. It should be stressed that in the vast majority of people, this altered state is harmless and often constructive; however, caution should prevail, as some people who have a susceptibility to psychosis or other related conditions may experience deteriorations in their mental states.

MDMA is a key that fits a different lock – in this case, a transporter protein that modulates the brain concentration of our internal neurotransmitter, serotonin. In binding to the serotonin transporter, MDMA causes a temporary flood of serotonin and thus has its own effects on our mood, memory and other brain functions.

The therapeutic effects of classic psychedelics and MDMA differ due to their different neuropharmacological actions. The therapeutic benefits of psilocybin seem to be related primarily to the downregulation of the network of brain regions known as the Default Mode Network, or DMN. This network is hypothesised to be involved in our sense of self and our self-narrative, and it appears to become more active in cases of certain mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. Thought processes tend to become more “rigid” such that our whole world view and way of being become less flexible; this seems to extend to related disorders such as problematic substance use, obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphia, and eating disorders. Hence, the administration of a classic psychedelic such as psilocybin, supported by psychotherapy, appears to disrupt these rigidified thought patterns in a positive way. A second factor is that the cellular connections between neurons in our brains are observed to wither away in the course of these mental illnesses, and that classic psychedelics seem to mediate the redevelopment of those lost connections and thereby counteract their psychological effects.

The therapeutic effects of MDMA appear to be much more related to the benefits of well-directed and administered psychotherapy. This seems to be particularly relevant to the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for which the most effective treatments tend to be based on forms of Exposure Therapy. By increasing concentrations of serotonin in the brain, and also modulating a range of neurohormones including oxytocin and prolactin, MDMA dramatically enhances the patient-therapist connection and also opens the “window of tolerance” that otherwise can limit the effectiveness of exposure-based psychotherapies.

Based on these different modes of action, we can start to explain why classic psychedelics such as psilocybin are well suited to the treatment of mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, distress associated with terminal illness, eating disorders, and problematic substance use, including alcoholism – all of which are postulated to involve increased inflexibility in thought patterns and emotional processing.

By contrast, MDMA is particularly well suited to the treatment of PTSD, including conditions arising from complex trauma but probably not so much dissociative conditions. Some current research using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to treat alcohol use disorder is also underway, and is yielding positive results; however, the theoretical basis for this approach is that alcohol and other substance use problems are frequently comorbid with long-term trauma conditions, and so the treatment of the problematic alcohol use (AUD) is essentially tied to the treatment of the underlying PTSD. It should be noted that there is no clear neurological basis for the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of AUD, as there is for the use of classic psychedelics in conjunction with psychotherapy.

Naomi: In drug trials for traditional medications, for conditions such as depression, there are a wide range of exclusion criteria. This effectively sees people with comorbidities not included. People with a diagnosis of PTSD may also meet criteria for depression, alcohol and drug abuse, and other anxiety disorders. Can you tell us something about inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trials you have been involved in?

Martin: The clinical trials studying classic psychedelics and MDMA have all aimed to apply the same level of methodological rigour as drug trials for traditional medications. Hence, broadly similar inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied in our studies, with some specific to psychedelics due to their profound effects on mood and cognition.

Typically, the inclusion criteria are fairly straightforward, and encompass age range (e.g. 18-65), index mental health condition, willingness to taper off current psychotropic medications, and currently being in the care of a psychiatrist, physician, or general practitioner.

The exclusion criteria are rather more extensive, as these psychedelic treatments are still largely experimental in a medical sense, and certain risks must be mitigated to ensure safe conduct of the trial. These include current or planned pregnancy in female participants; current use of a range of interacting medications; comorbid problematic substance use; long-term or very recent psychedelic use; cardiovascular, liver or kidney disease; personal or family history of psychosis/schizophrenia; certain personality disorders that might compromise the therapeutic alliance; and others that relate primarily to participant safety, but also – such as current participation in another clinical trial – that could compromise study integrity.

In many cases, such exclusion criteria might be regarded as too restrictive and not representative of real-world patients. This is true to a degree, but for better or worse, it is the currently accepted framework for clinical research leading to approved medical interventions. As a postscript, it should be noted that classic psychedelics are well-recognised to have negligible toxicity, so assuming they are eventually approved for therapeutic use, we can expect certain restrictions applied in clinical research to be relaxed in clinical practice.

Naomi: You are currently involved in a clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. Can you tell us about the trial?

Martin: Actually, I’m involved in two studies of psilocybin-assisted therapy (PAT) for TRD, both at Swinburne University and both involving multidisciplinary researchers from a range of institutions. The first, an open-label study in 15 participants, was launched just prior to the pandemic and, understandably, took some time to take shape and commence recruiting. It is now well underway, and involves two dosing sessions of 25 mg psilocybin with supportive psychotherapy, and augmented by a program of preparatory and integrative psychotherapy in line with the broadly accepted protocol for PAT. The second study, a multisite randomised-controlled trial in 160 participants, is in the planning stage and is due to start recruiting in July 2023. It will compare the effects of two versus three doses of 25 mg psilocybin plus psychotherapy, with those of an inactive placebo, also with psychotherapy.

Both studies will explore the effects of PAT on depression utilising a range of psychological measures, including depression and anxiety scores, quality of life, degree of disability, incidence of mystical experience, intensity of altered state of consciousness, and a range of health economics indices.

We expect that these studies will provide insights into the application of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy in the Australian context, and hopefully will inform health policy in relation to the provision of these therapies in future.

Naomi: Finally, what trajectory do you see for psychedelic assisted psychotherapies in Australia over the next 5 years – 10 years?

Martin: A week ago, I would have answered that we are on a steady course of research, hoping to make an Australian contribution to the global research effort in psychedelic medicine and anticipating that Australia would take its place among the nations that eventually approve psychedelic-assisted therapies for the treatment of a broad range of mental health conditions over the coming 5 years.

Research conducted mostly in the USA, UK, Switzerland, Canada and Israel, but now also well underway in Australia, has generated steadily accumulating evidence that psychedelic-assisted therapies can assist the broad range of mood disorders and associated conditions that we have discussed here. On this basis, there appeared to be a good chance that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy would be approved for PTSD, and psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy would be approved for depression (and probably end-of-life distress), in several jurisdictions including Australia. One could predict that approvals of PAT for a broader range of conditions would follow over the 10-year time frame, and that a number of other psychedelics – “legacy” compounds such as mescaline and LSD, as well as entirely novel psychedelics that are currently being designed and tested in labs around the world – also could be considered and probably approved for medical use.

The landscape has changed dramatically, however, following the announcement last week by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of its decision to reschedule psilocybin and MDMA from Schedule 9 (Prohibited Substances) to Schedule 8 (Controlled Medicines) on July 1, 2023. This decision, which essentially places Australia at the forefront in terms of reclassifying psychedelics worldwide, will pave the way for Authorised Prescribers – who, at this stage, must be psychiatrists – to administer psilocybin and MDMA for the treatment of Treatment-Resistant Depression and treatment-resistant PTSD, respectively. At this early stage, the TGA has provided scant guidance regarding any requirement for psychotherapy in conjunction with the administration of these medicines, nor indeed any specification in terms of therapist (or psychiatrist) training, treatment protocols, follow-up, or tracking of therapeutic outcomes to inform future development in the field.

As someone who has been working in the psychedelic research space for just on twelve years, I must say that given these recent developments, I now have no way of predicting the trajectory of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies in Australia over the next 5-10 years with any confidence at all. I expect that the ongoing development of alternative psychedelics for medical application will continue to take place, but in the meantime, I can only hope that the consequences of the TGA decision in relation to psilocybin and MDMA will match the hopes and aspirations of those who have supported it so strongly – some would say excessively so – over the past two years.

To paraphrase a former Prime Minister of Australia, “there’s never been a more exciting time to be involved in psychedelic medicine!” I expect the excitement will continue for some time to come.