A previous article explored organisational, interpersonal and personal responsibilities in addressing Vicarious Trauma (VT), compassion fatigue (CF) and burnout (BO). In this article, the authors reflect on the VT experience of lawyers and mental health professionals working with victim-survivors of sexual abuse, harassment, assault and rape. Josh Bornstein is Principal lawyer in Industrial Relations and Employment Law at Maurice Blackburn, practicing in this field for over 20 years. Naomi Halpern is director of Delphi Training and Consulting. She has over 30 years’ experience working with victim-survivors of trauma and abuse.

In 1990, US clinical psychologists Laurie Anne Pearlman and Lisa McCann coined the term vicarious trauma through their research exploring the impact of therapists’ work. Pearlman described in an article by Dhruti Shah in The Guardian “We began to understand, in talking with our colleagues, that we were taking on the trauma experiences of our clients, and that we were feeling deeply affected in ways that changed our outlook on life and our experience of ourselves as people in the world, and also our ability to manage our feelings in a constructive way. I was always a very trusting person, but I started to feel like questioning ‘What is that guy doing over there in that park with that young girl and is that a healthy relationship?’ and so on.” Since this time, VT has been recognised in professions beyond mental health.

The second author relates to Pearlman’s experience. After some years working with sexual abuse victim-survivors, she recalls travelling on a tram one evening and idly observing fellow passengers. Her gaze stopped on a man and the thought popped into her head, ‘I wonder if he’s a paedophile?’ She was shocked and ashamed by the thought. Over time she noticed that her mind would drift to the content of clients’ sessions out of work hours, misreading words or mishearing dialogue on television, the meaning changing to something unpleasantly sexualised. These unexpected intrusions crept up over time until she understood that her work was having a profound effect on her way of being in, and experiencing, the world.

As a lawyer who frequently represents victims of sexual abuse, sexual assault, and sexual harassment, the first author describes the challenge for himself and other lawyers in managing their emotions. He recounts routinely listening to accounts of terrible mistreatment and witnessing first-hand the impact of that treatment on the health of the women he and colleagues assist. He recalls a time ten years ago, ‘I walked into a conference room to meet for the first time with a woman who had been sexually harassed by a group of men. Prior to the meeting I had been provided with a dossier describing the events. It was sadistic and sickening. When I walked into the conference room, the woman was seated. I introduced myself. She looked up at me and said, “I don’t want to live anymore”. She began to sob and soon her body was shaking uncontrollably. I was distressed at her distress and my eyes filled with tears. I struggled to maintain my composure. For a time, I couldn’t speak. Then I said, “We’re going to go after the bastards that did this to you”.

The experience of losing his composure sent him on a journey in which he discovered the concept of vicarious trauma. Since that time, along with his colleagues, he has learnt more about what they can do to manage the risks of bearing witness to the trauma of their clients.

Both authors came to a crossroads in their different roles with victim-survivors, recognising the imperative of not only doing the best that they can for clients but also of taking care of themselves in the process. A key component of self-care is setting clear and consistent boundaries and understanding what we can and cannot do in our roles.

The first author is aware that by the time a woman seeks legal advice about sexual harassment, her mental health will be compromised. Discussion about mental health, trauma and the legal system forms a compulsory part of the first meeting. He explains that in these situations having strong medical support in place is even more important than having good legal support. Most women already have the support of a GP, psychologist or psychiatrist but if not, he advises that it is a must. He writes, ‘It’s not really legal advice but I offer it anyway’. While not legal advice it is trauma informed practice in the legal context. It is being clear about what a lawyer can and cannot provide. This serves as a protective factor for both the lawyer and the client.

The second author advises mental health professionals to provide clear information about clients’ rights and responsibilities at the outset of commencing therapy. These may look different depending on whether they work in an agency or in private practice. Information would include cancellation policies, fees, availability regarding contact between sessions and other practical considerations. Additionally, providing information about therapy and some of the challenges or difficulties that may arise, and how to make a complaint, is crucial. This practical information is part of establishing the therapy contract. Like the first author’s advice about the importance of having mental health support during the legal process, it assists to define the parameters of the therapeutic relationship which protects the client and the therapist in what is a complex relational dynamic.

There is no roadmap for lawyers to navigate assisting a client through a legal system that is a complex beast that can’t be controlled and, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to supporting victim-survivors. Pursuing a sexual harassment claim is inherently traumatic not the least because the victim is required to revisit the source of trauma. Victims of sexual crimes and misconduct experience immense fear, shame and guilt that can weigh on them for years.

The #MeToo movement has tried to throw off the shackles of shame and has undoubtedly galvanised more women to speak up and take action. The first author notes that many mental health professionals caution rape victims against pursuing a criminal prosecution because of the risk of failure and exacerbating the harm to health. He shares their concern. The second author recalls numerous conversations with clients during therapy about their thoughts around pursuing action through the criminal justice system. She recalls one client who came to see her after a judge found her father not guilty of sexually abusing her as a child. It was apparent to the second author she had not been emotionally, psychologically or physically resourced to withstand a court case. The outcome of the case compounded already extreme levels of distress and trauma.

Notwithstanding numerous attempts to modify the legal process in sexual violence cases to reduce risks of further harm to victims in the legal system, such as remaining anonymous, giving evidence via video link, having a support person or therapy dog close by, and prior sexual history being inadmissible, the first author notes there are still many pitfalls. These include spurious assumptions about the conduct of a “typical” offender or “typical” victim finding their way into criminal trials as witnessed recently with the prosecution brought against Bruce Lehrmann.

The first author states that the fact that the legal arena can be so brutal on victims of sexual assault has impacted him profoundly. He writes, ‘It has changed the way I practise law. While I don’t have control over a range of external factors, I now try and minimise the brutality for my clients and make sure that they are supported by health professionals while we pursue a case.’

There is a huge unmet demand in the labour market for legal assistance. The first author acknowledges that Maurice Blackman can only take on a small percentage of those who contact the firm. The legal system is highly expensive and invariably the defendants are far better resourced. One way Maurice Blackburn helps ameliorate these issues is employing a team of pro bono lawyers who staff their Social Justice Practise.

The mental health system also falls short in providing victim-survivors the care required. Medicare rebated sessions have been reduced from twenty to ten a year. Sexual assault centres and psychologists, social workers, counsellors, and psychiatrists in private practice often have lengthy wait lists. Long-term therapy is unaffordable for many. The limitations, constraints and inadequacies of the legal and mental health systems appear to be as much a contributing factor or exacerbator in legal and mental health professionals VT profile as the distressing stories and sometimes challenging presentations of clients.

So how do lawyers and mental health professionals support themselves with managing work-related stress, VT and not descend the slippery slope into CF or BO? The first author says, ‘Losing cases is never fun. I try to take on cases that I think will succeed and most of the time it pans out that way. Settlements are always a compromise and so usually all parties feel that they didn’t achieve everything that they wanted. That said, there are some cases in which the outcome is unjust for one reason or another. And sometimes I have strong feelings about those cases. With experience, I have learnt to regroup and keep going.

And yet, for all of that I have optimism. My clients and I have had a lot of success in resolving civil claims for sexual harassment – including in cases of workplace rape and sexual assault. Many such cases settle before trial and in pursuing them, we manage to avoid some of the harm caused in the criminal law system. For the first time in my career, we have succeeded in sexual harassment claims against serving and former judges including claims against a judge of the High Court. Those cases have sent shockwaves through the courts and the legal profession generally, triggering significant cultural change. Recently the federal parliament has enacted major reforms to sexual harassment laws which will impose stronger obligations on employers to proactively reduce sexual harassment and gender discrimination in the workplace. Slowly but surely, our culture is changing’.

The second author reflects on the similar and different aims and goals of a legal case and therapy. Both seek to assist clients to reach an outcome that is meaningful and assists her / him/ they to move forward in their life. A successful legal or therapeutic outcome (whatever that means for the client), does not change the past nor heal all hurts or wounds. The second author says, ‘A therapist’s first responsibility is to attend to Self, to address their own wounding, which in turn reduces the risks of problematic countertransference responses and stepping on the victim-rescuer-persecutor triangle. Case consultation and VT support are vital for mental health practitioners. Supporting themselves also assists therapists to not project their wishes or hopes for the client and mistaking these as measures of ‘success’.’

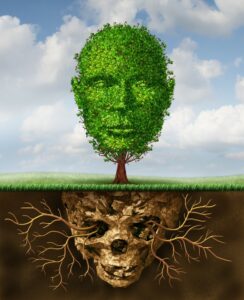

Lawyers and mental health professionals are vulnerable to experiencing VT at some point in their work with trauma clients. It is easy to focus on the risks, pain and distress that can arise from this work. It is also important to remind ourselves of the profound honour it is to accompany clients as they navigate their experiences. To marvel at the strength and tenacity of the human spirit, including during those times when we fear the person is holding on by the skin of their teeth. There is no doubt that we can experience VT. It is also true that we can experience ‘vicarious resilience’, a positive transformation in our worldview and spirituality in response to walking alongside and helping others live through trauma.

Two-part vicarious trauma and resilience training for mental health professionals and lawyers:

Befriending the Tiger: Vicarious trauma, resilience and self-care on the frontline

20 July and 27 July 2024 | 9.00am – 1.00pm AEST