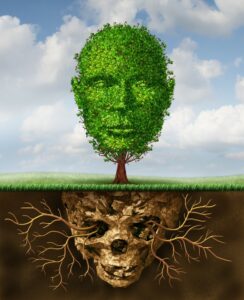

Moral injury is not a weakness. Concern for the wellbeing and safety of others is central to human relationships. For all democracy’s failings, moral principles, ethics, values, rule of law and empathy for others are the foundations upon which civil society is built. Viktor Frankl said, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” (1). Moral injury is, therefore, a consequence of humanness.

Differentiating Moral Injury from other psychosocial risks in the workplace

Moral injury may co-occur alongside psychosocial risks including secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue and burnout. It is useful to differentiate these experiences as healing is unique, nuanced and often requires a multi-layered approach.

Secondary traumatic stress (STS) emerges from indirect exposure to another person’s trauma, often through listening to traumatic stories, witnessing the pain, or from reading medico-legal reports, victim impact statements and viewing images (2). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 (DSM 5-TR) includes STS under Criterion A, describing it as “repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event/s”. This definition allows those who have not directly experienced a trauma to meet criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD (3).

Vicarious trauma (VT) is the gradual, long-term impact of repeated exposure to traumatic content. It causes deeper cognitive shifts than STS, altering the way an individual perceives themselves, others, and the world. VT can cause a person to feel that the world is not safe, accompanied by fear of being unable to protect self or loved ones from harm. VT can cause a sense of personal freedom being constricted (due to safety concerns), or that one’s work alienates self from others. Professions where confidentiality is key can contribute to a sense of alienation. Protecting others from distress and/or others not wanting to hear distressing stories can exacerbate feelings of alienation. Working with a demographic that does not elicit empathy and compassion from society can be an alienating factor (4).

Compassion fatigue (CF) is a state of profound emotional and physical erosion arising from exposure to the suffering of others. It is mostly associated with professionals who are in care giving roles and professions exposed to the suffering of others (5). Symptoms include emotional and physical exhaustion, irritability, cynicism, emotional overload or emotional shutdown. CF reduces the capacity to feel compassion and empathy for those a person is assisting, which may subsequently extend to family and friends.

Whereas CF is a STS response, burnout (BO) is a general state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged stress. BO is included in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon. It is described as, “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”. It is not classified as a medical condition (6). BO is a risk in work environments where there are high expectations of output, often accompanied by lack of resources, supervision, recognition, financial remuneration not commensurate to workload or responsibility, insecure contracts and systemic or cultural issues such as bullying, discrimination and harassment.

Moral injury is not a mental health diagnosis. The term does not appear in the DSM-5-TR (but will shortly be listed under Z65.8 Moral, Religious, or Spiritual Problem, to acknowledge when clinical issues have a moral or spiritual component) or ICD-11. People who have sustained a MI often exhibit symptoms of PTSD but do not meet criteria for a PTSD diagnosis. PTSD criteria do not include ‘moral anguish’ the core of MI, accompanied by feelings of guilt, shame, anger and disgust toward self and/or others. As noted in part one, MI has recently been associated with the ICD-11 diagnosis complex-PTSD (c-PTSD), in the regions of disturbances in self-organisation, interpersonal difficulties, negative self-concepts around beliefs of worthlessness or failure and difficulty managing and regulating emotions such as extreme anger, sadness, or anxiety, and feelings of worthlessness, shame and guilt (7).

Assessing moral Injury

Self-assessment tools for STS, VT, CF, BO (8, 9, 10, 11) are freely available. Some assessments focus on one experience while others incorporate two or more. Moral injury self-assessments include the Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS) (12), Moral Injury Outcome Scale (13), Occupational Moral Injury Scale (OMIS) (14) and Moral Injury at Work Scale (MIWS) (15).

These psychosocial hazards often present with similar symptoms. This is true of many physical medical conditions. Severe headaches may stem from migraine, dehydration, poor posture, brain aneurysm, stroke, or infection. Furthermore, a person may have a primary diagnosis and comorbidity; a condition that sits alongside the primary diagnosis which could be a consequence of the primary diagnosis or a separate condition that influences treatment. A person with a primary diagnosis of chronic kidney disease may also have secondary conditions requiring treatment such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

A person who has sustained a MI may additionally experience any of the above psychosocial hazards and be at further risk of developing a mental health condition. In addition to c-PTSD other potential mental health conditions and behaviours include anxiety, depression, substance abuse, insomnia, gambling, changes in eating habits and suicidality. Additional mental health impacts, whether caused by the MI or pre-existing, will require assistance alongside support for the MI.

Personal factors, including social, family and professional supports, current life circumstances and past trauma can also influence the impact of, and recovery from MI.

How is moral injury experienced?

The International Centre for Moral Injury definition of moral injury, “a profound sense of broken trust in ourselves, our leaders, governments and institutions to act in just and morally ‘good ways’ and the experience of sustained and enduring negative emotions – guilt, shame, contempt and anger – that results from the betrayal, violation or suppression of deeply held or shared moral values” (16) reflects the multi-faceted experience of MI. Questions to guide an individual in forming an understanding of the nature of their wounding might include:

- Was the moral injury caused by an act/s of commission (I was involved in some capacity in a wrongdoing or harm).

- Was the moral injury caused by an act/s of omission (I was not actively involved in a wrongdoing or harm but I but didn’t do anything to prevent it).

- Is there something I should have done or not have not done?

- Was there something I could have done or not done?

- Why did I do or not do something?

- Did I feel I couldn’t do anything out of fear for myself and/or fear for others?

- If I acted to protect myself was that a smart decision or do I feel it was a cowardly act?

The morally injured person may have self-directed responses, “I’m at fault”, accompanied by feelings of guilt, shame, self-disgust and anger toward self. Responsibility may be externally directed, toward an individual or an organisation. When responsibility is with another/organisation it does not necessarily mean the morally injured individual does not still apportion self-blame, often with thoughts and beliefs, “I should have known”, “I should have done something”, even when it is clear they couldn’t have known or done something prior to the event/s. Self-directed or externally directed responses may be correctly or incorrectly apportioned. How others perceive their actions/inactions may ease or add to suffering. The correctness or incorrectness of answers to these questions may or may not assist with how the morally injured person feels and the meaning they make from the experience. Who is the arbiter of truth to these questions?

Personal pathway to healing from moral injury

While self-care practices, and reducing stressors in one’s control are always helpful, they will not prevent or heal a MI. Self-assessments may be a useful starting point, helping to tease apart interconnected threads.

Whether the MI arises from acts of commission or acts of omission, it ignites an existential or faith crisis, shaking deeply held values, morals and beliefs. Sitting in a space where everything one has known and held dear is turned upside down is profoundly disturbing, painful and disorienting. Humans seek certainty, stability and safety. Experiences such as an unexpected health diagnosis, life altering accident or a betrayal such as an affair, shake our sense of certainty and identity. This is true of MI.

It is natural to attempt to protect ourselves from emotional pain. Sometimes, a seemingly effective way to avoid pain is to push others away, to alleviate fear of rejection and accompanying intensity of pain. Finding a pathway, stepping toward and moving away allows pacing to gently build capacity to work with the injury and take the risk of allowing loved ones and trusted confidantes to be alongside for support.

Therapy may assist in exploring the existential or faith crisis and understand drivers that influenced a person to do or not do, act or not act, in particular ways. There is no ‘moral injury’ therapy, and as with any human distress, there is no one size fits all approach. A therapeutic approach that works for one person will not assist another. This is neither a fault in the therapeutic approach, nor the person. If the first therapist or modality doesn’t resonate, it is encouraged to be open to, and willing to try another. Modalities including psychodynamic psychotherapy, sensorimotor psychotherapy, Internal Family Systems (IFS), Eye Movement and Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR), Narrative Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Emotionally Focussed therapy (EFT), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (T-F CBT) or combinations of, are some options. A MI may tap into earlier life experiences and healing take several unexpected twists and turns.

Afghanistan veteran, Matt Zeller says, “A moral injury is really insidious because it’s an injury of the soul. So it’s the hardest to treat. You can’t take a pill for it. The only way to truly heal from a moral injury is through acts of service, doing good deeds for others in need.” (17).

Part of healing may lead to avenues to make amends – irrespective of ‘fault’. Making amends can take many forms. It might be an apology. It might take the form of activism, or writing about the experience, being public about what occurred or as Zeller says, through acts of service. Healing is coming to a place of peace and acceptance, which is not excusing, justifying, saying what happened was OK or conditional on being forgiven by others, but an internal space where the burden and pain is integrated. Healing from MI is a personal process. Reaching a place of clarity about what one is and isn’t responsible for, not only intellectually but also emotionally is key. Grieving for what did or didn’t happen, about what one did or didn’t do, knew or didn’t know, actions taken or not taken, what was one’s own, or another’s responsibility is central to healing. The road map will look different for everyone, even when the terrain appears similar.

“In order to heal, you must hurt, in order to love you must break open, and in order to have peace you must face chaos“ (18).

Organisational responses: Institutional Betrayal vs Institutional Courage

When an incident harms an employee or the public, be it accidental, a failing in policy, procedure, or organisational culture, how the organisation addresses the situation makes a difference, for better or worse.

Organisations may feel caught between a rock and a hard place, managing reputational damage and financial risk, with repairing harm. This can create moral and ethical dilemmas beyond the original incident for those charged with managing the response, creating a morally injurious ripple effect throughout an organisation. Viewing reputational and financial risk management and taking responsibility in whatever form is required, as if they conflict with one another, misses the opportunity to address the wrong and make meaningful change. An institutions response may exacerbate or ameliorate the impact of moral injury.

In his book, “Working For The Brand: how corporations are destroying free speech”, Bornstein cites numerous examples of organisations compounding damage to their reputation through doubling down when a wrongdoing enters the public domain. During the COVID-19 pandemic QANTAS received two billion dollars in jobseeker payments with one hand while pushing 1800 baggage handlers out the door and outsourcing cheaper labour with the other hand. The case went all the way to the High Court. The flagship Australian airline was ordered to pay $120 million compensation to the sacked workers. QANTAS said they accepted the decision of the High Court and said, “As we have said from the beginning, we deeply regret the personal impact the outsourcing decision had on all those affected and we sincerely apologise for that.” It was a great victory for the workers. However, Bornstein argues that some companies, no matter the short-term reputational damage, are too big to fail or suffer long-term consequences for bad behaviour, with litigation and fines factored in as the cost of doing business. QANTAS still came out in front. On Monday 18 August 2025, federal court Justice Michael Lee, imposed a record breaking $90 million dollar fine saying, “Qantas had shown the wrong kind of sorry, whereby it worried more about the impact on the company rather than the impact the case had on the illegally sacked workers” (20).

Similarly, the ABC was found to have unlawfully sacked journalist, Antoinette Lattouf. Insidious behaviour of senior ABC management came to light during court proceedings. The ABC spent over a million dollars of public money defending the indefensible. Riding out the storm, knowing the dust will eventually settle, and another story will take its place in the headlines, is a business strategy. The moral injury and other long-term impacts for those who were harmed won’t subside once the spotlight has dimmed.

Freyd describes this behaviour as institutional betrayal. She outlines an antidote to institutional betrayal, institutional courage. Institutional courage is defined as, “an institution’s commitment to seek the truth and engage in moral action, despite unpleasantness, risk, and short-term cost. It is a pledge to protect and care for those who depend on the institution. It is a compass oriented to the common good of individuals, the institution, and the world. It is a force that transforms institutions into more accountable, equitable, effective places for everyone.” (21).

The eleven steps to promote institutional courage outlined below can be applied within any institution, public or private. They complement trauma informed values and principles of safety (physical and emotional), trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, empowerment and cultural considerations (22).

11 steps to promote institutional courage (23).

1. Comply with civil rights laws and go beyond mere compliance; beware risk management

2. Educate the institutional community (especially leadership)

3. Add checks and balances to power structure and diffuse highly dependent relationships

4. Respond well to victim disclosures (and create a trauma-informed reporting policy)

5. Bear witness, be accountable, apologise

6. Cherish the whistleblowers; cherish the truth tellers

7. Conduct scientifically-sound anonymous surveys

8. Regularly engage in self-study

9. Be transparent about data and policy

10. Use the organisation to address the societal problem

11. Commit on-going resources to 1-10

These are actionable steps to create a culture of trust, safety, effectiveness, productivity and wellbeing. They will not eliminate all risk of moral injury in the workplace but when an incident occurs the injured party will receive the acknowledgment, help and support required.

In Freyd’s 2024 webinar for Delphi Training and Consulting, Moving from Institutional Betrayal to Institutional Courage: Addressing Sexual Violence and Gender Discrimination, (24) she quoted from a letter written by the President of Oregon State University, Ed Ray, apologising to past student, Brenda Tracy for the behaviour of OSU in responding to a gang rape by four OSU football players in 1998. Despite strong evidence and confessions, the District Attorney refused to prosecute. Brenda was never told her rights or informed when her evidence was destroyed three years before the statute of limitations expired (25). Noone from the OSU talked to Tracy at the time of the rapes.

The letter reads;

“Dear Brenda,

Oregon State officials are very grateful that you took time to meet with us. We are so sorry for what you experienced in 1998 and have lived with since. What we have learned recently of your suffering is heart breaking, and your bravery inspires us. We are also grateful to you for raising the public dialogue about the consequences of sexual violence in our society and for raising a discussion of how society can better assist survivors of such violence. While we cannot undo this nightmare, we apologize to you for any failure on Oregon State University’s part to better assist you in 1998.

As promised a few weeks ago, we conducted an exhaustive review of the facts of how OSU handled this matter 16 years ago. This review was completed this past Friday, and we want to share the results of that review with you”.

Following the apology, Ray hired Tracy to be a consultant to address improving OSU policies and procedures which led to important innovations and changes at the university.

Institutional courage in action.

1. Frankl, V. (1946) Man’s Search for Meaning, Verlag für Jugend und Volk (Austria), 1st Edition

2. Hensel JM, Ruiz C, Finney C, Dewa CS. Meta-analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. J Trauma Stress. 2015 Apr;28(2):83-91. doi: 10.1002/jts.21998. PMID: 25864503.

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), (2022) American Psychiatric Association

4. Pearlman McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140

5. Figley, C. (1995) Compassion Fatigue: Coping With Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder In Those Who Treat The Traumatized, Taylor and Francis Ltd

6. WHO, (28 May 2019) Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases, https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

7. Jovarauskaite L, Murphy D, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene I, Dumarkaite A, Andersson G, Kazlauskas E (2022).“Associations between moral injury and ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD among help-seeking nurses: a cross-sectional study”. BMJ Open. 12(5): e056289. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056289. PMC 9086640. PMID 35534083.

8. Ting, L., Jacobson, J. M., Sanders, S., Bride, B. E., & Harrington, D. (2005). The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS): Confirmatory Factor Analyses with a National Sample of Mental Health Social Workers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 11(3–4), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v11n03_097.

9. Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute Inc., Burnout, compassion Fatigue and Vicarious Trauma Assessment. www.ctrinstitute.com

10. Figley, C. Compassion Fatigue Self-Test for Practitioners, (1996) American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress

11. Adapted from MindTools: Essential skills for an excellent career. Burnout Self-Test – https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTCS_08.htm

12. Norman, S. B., Griffin, B. J., Pietrzak, R. H., McLean, C., Hamblen, J. L., & Maguen, S. (2023). Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS). Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.govMIDS

13. Litz, B. T., Plouffe, R. A., Nazarov, A., Murphy, D., Phelps, A., Coady, A., Houle, S. A., Dell, L., Frankfurt, S., Zerach, G., Levi-Belz, Y., & Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium (2022). Defining and Assessing the Syndrome of Moral Injury: Initial Findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 923928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.923928

14. Thomas, Victoria & Bizumic, Boris & Quinn, Sara. (2023). The Occupational Moral Injury Scale (OMIS) – Development and Validation in Frontline Health and First Responder Workers. 10.31219/osf.io/ht7ne.

15. Snoeyink, Megan J., “Uncovering Moral Injury at Work: The Development and Initial Validation of the Moral Injury at Work Scale (MIWS)” (2025). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 6797. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3920

16. Litz, Brett T.; Stein, Nathan; Delaney, Eileen; Lebowitz, Leslie; Nash, William P.; Silva, Caroline; Maguen, Shira (December 2009). “Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy”. Clinical Psychology Review. 29(8): 695–706.

17. Zeller, M., (2022) Riding the Afghan Underground Railroad, Sesan 7 – Episode 7 https://crazygoodturns.org/episodes/afghan-underground-railroad

18. Unknown

19. Bornstein, J. (2024) Working For The Brand: how corporations are destroying free speech, Scribe

20. Khadem, N. 18 August 2025, Federal Court fines Qantas $90 million for illegally outsourcing ground handling workforce, ABC

21. Freyd, J. J., & Smidt, A. M. (2019). So you want to address sexual harassment and assault in your organization? Trainingis not enough; Educationis necessary. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(5), 489–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1663475

22. Harris, Maxine; Fallot, Roger D. (2001). “Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift”. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 2001(89): 3–22.

23. Freyd, J.J. (2018; updated 2022) When sexual assault victims speak out, their institutions often betray them, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/when-sexual-assault-victims-speak-out-their-institutions-often-betray-them-87050

24. Freyd, J. & Bornstein, J. (2024) Moving from Institutional Betrayal to Institutional Courage: Addressing Sexual Violence and Gender Discrimination, Delphi Training and Consulting

25. Brenda Tracy https://brendatracy.com/

Updated 18 August 2025